Prime Minister Anthony Albanese called the situation “disappointing.” Treasurer Jim Chalmers described it as “concerning.” But for Australia’s mining sector, China’s September 2025 directive to suspend BHP iron ore purchases represents something far more serious.

It’s a shot across the bow.

The move signals a calculated pressure test from Beijing. One that exposes the fragile economics underpinning Australia’s most valuable export relationship. With nearly 60% of Australia’s iron ore flowing to Chinese steel mills, the implications extend well beyond corporate negotiations over pricing. They cut to the heart of Australia’s export-dependent economy and China’s strategic quest for supply chain sovereignty.

The BHP Ban: Commercial Dispute or Strategic Signal?

In late September 2025, the China Mineral Resources Group (CMRG) reportedly instructed domestic steelmakers to halt all new purchases of BHP’s dollar-denominated iron ore cargoes. The directive affected not just future contracts but shipments already departed from Australian ports.

Iron ore stockpiles at Australian port facilities.

The timing was notable. It followed a breakdown in contract negotiations between BHP and CMRG, a state-owned buyer established in 2022 specifically to consolidate China’s purchasing power in iron ore markets.

BHP supplies roughly 13% of China’s iron ore imports. Replacing that volume overnight would be impossible for either side. Yet the ban persists, with existing landed cargoes the only BHP material still tradable in China.

Market reaction was measured. BHP shares dipped just 1.1% following the announcement, suggesting investors view this as a negotiating tactic rather than a permanent rupture.

Western Australia Premier Roger Cook described it as “strategic gamesmanship” aimed at securing better pricing terms. But the episode reveals deeper tensions about market power, pricing mechanisms, and long-term supply security.

Australia’s Iron Ore Dependency Runs Deep

The numbers tell a stark story.

Australia exported $138 billion worth of iron ore in 2023-24, with China accounting for approximately $115 billion of that total. Iron ore represents nearly 60% of Australia’s merchandise exports to China, dwarfing other commodities like LNG ($10.8 billion) and coal ($2.2 billion).

According to UN COMTRADE data, China imported $79.64 billion worth of iron ore from Australia in 2024, representing about 60% of China’s total iron ore imports.

The concentration is geographic too. Nearly all of Australia’s iron ore comes from Western Australia’s Pilbara region, where mining giants BHP, Rio Tinto, and Fortescue Metals Group operate vast operations.

This dependency cuts both ways. China relies heavily on Australian ore due to its quality, proximity, and established infrastructure. Brazilian ore, while significant, cannot fully substitute Australian supply in the short term.

But the balance is shifting.

Geopolitical Factors: From Trade War to Strategic Competition

The iron ore relationship exists within a broader context of deteriorating Australia-China relations. Between 2020 and 2022, China imposed trade barriers on Australian wine, barley, beef, timber, and coal, costing exporters up to $20 billion annually.

Iron ore was notably spared. Not out of goodwill, but necessity.

China couldn’t easily replace 60% of its iron ore supply. Australia couldn’t easily replace its largest customer. The result was an uneasy interdependence that has held despite political tensions.

However, China has been working methodically to reduce this vulnerability.

In 2022, Chinese authorities created CMRG to centralize iron ore purchasing and increase bargaining power. Chinese companies have invested heavily in overseas mines, particularly in West Africa. And Beijing has made clear its intention to reduce Australian supply from 60% to around 40% by 2030.

Senator Matt Canavan and businessman Clive Palmer have publicly suggested Australia should tax or restrict iron ore exports. While marginal domestically, such statements are taken seriously in Beijing and accelerate Chinese diversification efforts.

The Ukraine conflict demonstrated how control over commodities carries strategic value. China views iron ore through this lens, recognizing its current dependency as a vulnerability to be managed.

Alternative Markets: Guinea’s Simandou Emerges as Game-Changer

China’s most significant diversification play centres on Guinea’s Simandou iron ore deposit.

Guinea’s Simandou iron ore

Described as the world’s largest untapped high-grade iron ore resource, Simandou could produce 120 million tonnes annually once fully operational. First shipments are expected in November 2025, with production ramping to 200 million tonnes per annum by decade’s end.

The project involves Rio Tinto alongside Chinese state-owned enterprises including China Baowu, the world’s largest steelmaker. This gives China equity control over a substantial new supply source while reducing reliance on Australian imports.

Simandou’s ore grades between 65-66% iron content, higher than much of Australia’s production. Rio Tinto has noted that 40% of Simandou’s resources are “well suited to meet DRI specification,” making them ideal for emerging green steel technologies.

Beyond Guinea, China is developing iron ore capacity in:

- Sierra Leone’s Tonkolili mine (13.7 billion tonnes estimated reserves)

- Gabon’s Belinga project

- Various Central Asian projects through Belt and Road investments

Brazil, the world’s second-largest iron ore exporter, is also expanding. Vale plans to bring 50 million tonnes of additional supply online over the next two years.

Combined with new Australian production from projects like Mineral Resources’ Onslow (35 million tonnes per annum capacity), global iron ore supply is set to surge significantly by 2026-2027.

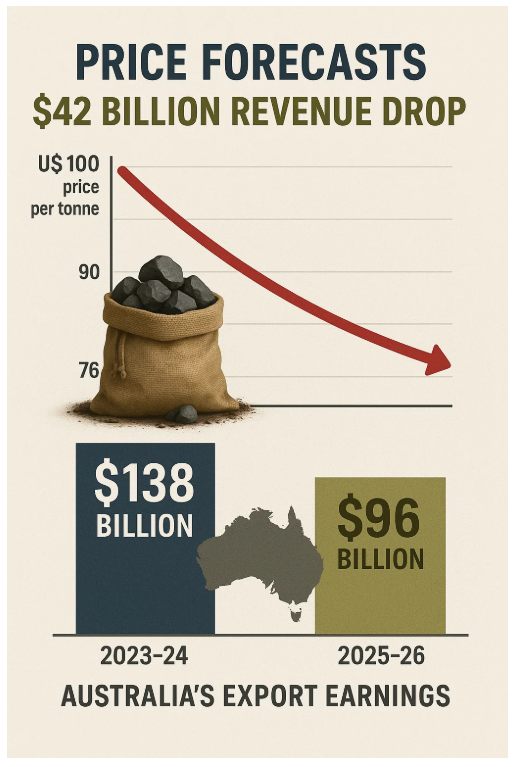

Price Forecasts: A $42 Billion Revenue Drop

The supply-demand imbalance has clear implications for pricing.

Australia’s Department of Industry, Science and Resources projects iron ore prices will decline from around US$100 per tonne currently to US$76 per tonne by 2026. This would reduce Australia’s export earnings from $138 billion in 2023-24 to $96 billion by 2025-26.

That’s a $42 billion revenue drop over two years.

Macquarie Bank forecasts a market surplus of 200 million tonnes over 2026-2028, with prices potentially falling to the US$60-70 range by decade’s end. Commonwealth Bank of Australia projects a long-term price of US$68 per tonne.

Even at these lower prices, major Australian miners will remain profitable. BHP, Rio Tinto, and Fortescue operate some of the world’s lowest-cost iron ore operations, with production costs around US$10-15 per tonne.

But the reduced export revenues will hit Australia’s federal and state budgets hard. Western Australia, which receives substantial royalties from iron ore mining, recently revised its 2025 price forecast upward to US$95 per tonne, but this appears optimistic given prevailing market conditions.

The Green Steel Revolution: A Longer-Term Threat

Beyond pricing pressures, Australian iron ore faces a structural challenge from steelmaking technology shifts.

Traditional blast furnace steelmaking uses Australia’s lower-grade hematite ore. But the global transition to low-carbon steel production favours direct reduction iron (DRI) processes, which require higher-grade ore.

Nearly 100 million tonnes of new DRI capacity are under construction globally, with commercial operations already running in China. DRI plants can use green hydrogen instead of coal, producing truly low-emission steel.

The problem? Only about 5% of the current seaborne iron ore trade meets DRI specifications. Around 95% of Australian iron ore production comes from hematite mines unsuitable for DRI without further processing.

Australia does have 40% of its iron ore resources as magnetite ore, which is more suitable for green steel technologies. But developing these resources requires significant capital investment and time.

Projects like the NeoSmelt collaboration between Rio Tinto, BHP, and BlueScope aim to make Australian hematite usable in DRI processes. However, the recent involvement of Woodside Energy suggests the project will initially use natural gas rather than green hydrogen, placing it at a competitive disadvantage to overseas green iron initiatives.

Guinea’s Simandou, Brazil’s high-grade deposits, and potential Middle Eastern green iron production using renewable energy all pose competitive threats to Australia’s lower-grade ore in the emerging green steel market.

As the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis notes, “the long-term future of Australia’s largest export depends on” solving this grade challenge.

Can Australia Diversify Its Customer Base?

While China reduces its Australian dependence, can Australia do the same?

The reality is sobering.

Japan and South Korea together import about 75 million tonnes of Australian iron ore annually, less than 15% of what China takes. India is largely self-sufficient in iron ore and unlikely to become a major importer soon.

Emerging Southeast Asian steel producers offer some potential, but the volumes are relatively small. The Australian government forecasts modest growth in regional steel demand, insufficient to offset any significant decline in Chinese purchases.

The economic geography is stark. China’s proximity to Australia and its massive steel industry made it a natural market. No alternative destination offers comparable scale or logistics efficiency.

This asymmetry explains why Australian officials responded so quickly to the BHP situation. Albanese emphasized wanting to see “Australian iron ore be exported into China without hindrance,” acknowledging the relationship’s importance to both economies.

For Australia, maintaining access to Chinese markets while encouraging diversification by China represents a delicate balancing act.

Investor Outlook: Navigating Uncertainty

For investors in Australian mining stocks, the iron ore situation presents both challenges and opportunities.

Major producers like BHP, Rio Tinto, and Fortescue remain well-positioned to weather pricing pressures given their low-cost operations. However, their earnings and dividends will decline as prices fall and volumes potentially shift.

Junior miners and explorers face tougher conditions. Projects that were viable at US$100 per tonne may struggle at US$70-75 per tonne. Capital availability for new developments is likely to tighten.

The green steel transition may create opportunities for magnetite producers and processing technology developers. Companies successfully adapting Australia’s ore for DRI processes could gain strategic advantages.

Currency movements add another variable. As a commodity currency, the Australian dollar typically weakens when iron ore prices fall, providing a natural hedge for local miners whose costs are denominated in AUD but whose revenues are in USD.

What Happens Next?

Several scenarios could unfold:

- Near-term resolution: BHP and CMRG reach agreement on pricing terms, the ban lifts, and trade normalizes. Most likely given mutual dependence.

- Prolonged standoff: The ban continues, with China gradually building alternative supply chains while Australian miners seek other markets and optimize costs.

- Broader escalation: Trade tensions expand beyond BHP to other Australian producers or commodities, triggering more aggressive responses from both governments.

The most probable outcome involves a negotiated settlement on the BHP situation followed by a gradual, managed decline in Australia’s iron ore dominance as Chinese diversification efforts mature and new global supply comes online.

Australia’s mining sector will adapt, but the era of unchallenged iron ore prosperity appears to be ending. The industry must navigate pricing pressures, technological transitions, and geopolitical complexity simultaneously.

For a nation where mining contributes over 10% of GDP and 60% of export value, these adjustments carry significant economic and political implications.

The iron ore trade that built Australia’s modern prosperity now faces its sternest test.

Also Read: Australia Takes Aim at China’s Lithium Processing Empire—But Can It Win?

FAQs

1.How much iron ore does Australia export to China?

Australia exports approximately 60% of China’s total iron ore imports, valued at around $115 billion AUD annually. This represents about 540 million tonnes of iron ore in recent years.

2.What caused the BHP iron ore ban?

The ban reportedly stems from failed contract negotiations between BHP and the China Mineral Resources Group (CMRG) over pricing mechanisms and terms. It’s viewed as a negotiating tactic rather than a permanent trade barrier.

3.Will iron ore prices fall in 2025?

Most forecasters predict iron ore prices will decline from around US$100 per tonne currently to US$76-80 per tonne by 2026, driven by increased supply and softening Chinese demand.

4.Can Australia find alternative markets for iron ore?

Limited alternative markets exist with sufficient scale. Japan and South Korea are established customers but import far less than China. India and Southeast Asia offer modest growth potential but cannot replace Chinese demand.

5.What is the Simandou project?

Simandou is a massive iron ore deposit in Guinea, West Africa, expected to produce 120-200 million tonnes annually once fully operational. It represents China’s primary strategy to diversify away from Australian supply.