Sixty years ago, a drilling rig punched through Western Australian rock and changed the nation’s industrial trajectory forever.

On 28 January 1966, Western Mining Corporation intercepted high-grade nickel at 133 metres depth near an abandoned gold town. The discovery transformed Kambalda from a ghost settlement into Australia’s first nickel mining hub, launching a metals boom that would produce over 1.6 million tonnes of nickel metal across six decades.

Today, as Indonesia floods global markets with cheap nickel and Australian operations shutter, Kambalda’s story offers sobering lessons about commodity cycles, geopolitical supply chains, and the brutal economics of mining.

The Accidental Discovery That Started It All

The Kambalda Nickel Industry began not with grand ambitions, but with rejected uranium samples.

In 1954, prospector George Cowcill submitted ore specimens to the Kalgoorlie School of Mines. The samples contained no uranium. Instead, geologist Bill Cleverly identified nickel-bearing gossan – oxidised ore that hinted at mineralisation below.

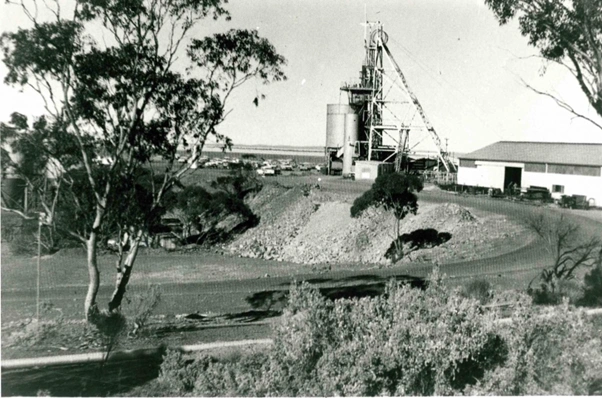

Historical drilling operations at Kambalda [Eastern Goldfields Historical Society]

For a decade, nothing happened. Then in 1964, Cowcill and prospecting partner John Morgan resubmitted samples to Western Mining’s Dr Roy Woodall. This time, the company acted. Drilling commenced in late 1965.

When that first high-grade intercept came through in January 1966, it sparked what Western Australian mining circles still call the “Nickel Boom.” The Department of Mines annual report described it as a “momentous event” that would reshape the state’s economic landscape.

By June 1967, Western Mining had commissioned a concentrator plant with 130,000 tonnes annual capacity. The official opening took place that September, attended by Premier David Brand. Construction costs reached $5.9 million – modest by today’s standards, but substantial for the era.

Building Towns, Fortunes, and Infrastructure

The Kambalda discovery triggered consequences far beyond the mine itself.

Western Mining constructed two purpose-built towns four kilometres apart. Kambalda East housed 300 residents by August 1967, built on the exact site where Percy Larkin had discovered gold in 1897. Kambalda West followed as ore discoveries pushed residential areas westward.

By 1972, concentrator capacity had expanded to 1.4 million tonnes annually. The operational success funded construction of the Kalgoorlie Nickel Smelter and Kwinana Nickel Refinery, creating an integrated processing chain that employed thousands.

At its peak in 1986, the deposit held 7% of the Western world’s nickel reserves. The mineralisation sat at the contact zone between ultramafic rocks and overlying volcanics – a geological setting that would become the template for nickel exploration globally.

Key milestones that defined Kambalda’s dominance:

- 1966: Discovery drilling confirms high-grade nickel

- 1967: First concentrate production begins

- 1974: Gold discovered in nickel shafts, leading to St Ives Gold Mine

- 1992: Concentrator processes 30 million tonnes, containing 930,000 tonnes nickel metal

- 2007: Forty years after opening, Western Australian nickel industry reaches $8 billion value

The success created ripple effects. BHP acquired Western Mining in 2005, absorbing the operation into its Nickel West division. Multiple junior miners acquired former Western Mining tenements, sustaining production through price cycles.

The Boom-Bust Cycles Begin

Nickel prices never stay stable. The Vietnam War drove 1960s demand. The mid-1970s saw sales decline and workforce layoffs despite rising stockpiles. Industrial action in the late 1980s centred on union opposition to seven-day mining operations.

In 1986, during a severe downturn, Western Mining closed the original Silver Lake Shaft – Australia’s first nickel mine. Twenty years of continuous operation ended as prices collapsed.

Gold production during the 1980s nickel slump kept Kambalda viable. The concentrator added gravity circuits to recover gold, demonstrating the diversification that would characterise the region’s future.

By 2000, Western Mining began divesting Kambalda assets. In 2003, mining operations ceased entirely, though the concentrator continued processing third-party ore. Mincor Resources acquired four mines in November 2000, intermittently working former Western Mining operations.

Low prices forced Mincor to place operations on care and maintenance in 2016. Six years later, in May 2022, mining resumed at the new Cassini deposit, 128 kilometres south of Kalgoorlie.

The Indonesian Flood Changes Everything

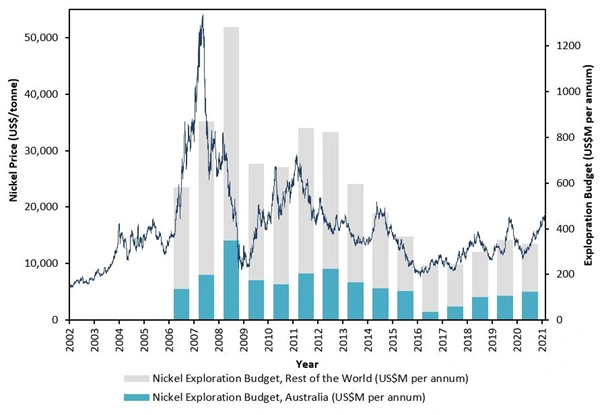

What killed Kambalda wasn’t depletion – it was Indonesia.

Between 2020 and 2024, Indonesia’s nickel production exploded from 31.5% to 60.2% of global supply. Chinese-backed investment in downstream processing followed Indonesia’s 2020 export ban, forcing a significant portion of Western production out of business.

By late 2024, London Metal Exchange nickel prices had plunged below US$14,100 per tonne – near five-year lows. Indonesian laterite nickel, produced cheaply using coal power, undercut higher-cost Australian sulphide operations.

The casualty list grew:

- BHP suspended Nickel West operations

- First Quantum put Ravensthorpe into care and maintenance

- Savannah mine shut down

- Australia’s annual nickel production collapsed from over 150,000 tonnes to approximately 60,000 tonnes

In January 2024, Wyloo Metals – owned by iron ore billionaire Andrew Forrest – announced plans to place Kambalda operations on care and maintenance by May 31st. Wyloo had acquired Mincor Resources for $504 million just six months earlier.

The shutdown terminated a supply agreement with BHP that ran through 2025. Wyloo’s 15,000 tonnes annual production capacity fell silent, ending nearly six continuous decades of nickel mining at Kambalda.

Nickel price trajectory showing Indonesian oversupply impact [Geoscience Australia]

What Indonesia Gets That Australia Doesn’t

Indonesia’s dominance stems from geology, policy, and timing.

Laterite nickel deposits require less capital to develop than sulphide deposits. Processing uses readily available coal power. The Indonesian government strategically banned exports of raw ore, forcing investors to build domestic smelting capacity.

By contrast, Australian operations face higher electricity costs, stricter environmental regulations, and sulphide processing that demands more sophisticated metallurgy. The carbon footprint remains lower, but markets haven’t consistently priced that premium.

Wyloo CEO Luca Giacovazzi acknowledged the challenge: “Indonesia has played a huge role in bringing new supply online, which has impacted the nickel price in the short term. The market has seen too much supply too quickly.”

In December 2025, Indonesia announced plans to cut 2026 nickel ore production by approximately 34% to 250-260 million tonnes. Whether this restores price equilibrium remains uncertain.

The Human Cost of Commodity Cycles

Behind production statistics sit communities built around mining.

Kambalda’s population peaked at over 4,000 during boom times. The 2021 census recorded just 2,468 residents across Kambalda East and West. The ANZ Bank branch closed in September 2018. Kambalda Airport was mothballed in September 2015.

Fly-in, fly-out operations replaced residential workforces, weakening community cohesion. Local businesses dependent on mine wages contracted. The town that nickel built faced existential questions about its future.

Yet Kambalda persists. The St Ives Gold Mine, discovered in 1974 in nickel workings, continues producing. Gold Fields operates one of Western Australia’s leading gold producers nearby. The Beta Hunt Mine delivered spectacular gold discoveries in recent years.

Other explorers maintain a presence. Lunnon Metals holds 100% mineral rights to Foster and Baker deposits, plus the historic Silver Lake and Fisher mines. In January 2025, Lunnon signed a mining agreement with the Ngadju people after three years of negotiations.

Can Australian Nickel Survive?

Industry observers offer cautious optimism grounded in structural realities.

Battery-grade nickel demand is forecast to triple by 2030. While lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries dominate Chinese EV production, nickel-rich chemistries (NMC, NCA) remain essential for vehicles requiring higher energy density and longer range.

Australian producers argue their nickel carries environmental advantages. Wyloo partnered with German platform Metalshub to market low-carbon nickel with transparent ESG credentials, positioning for price premiums as supply chain scrutiny intensifies.

The geopolitical dimension matters too. Western economies increasingly prioritise secure mineral supplies from allied nations. Indonesia’s concentration of 70-80% of nickel supply creates a strategic vulnerability that governments recognise.

Factors that could revive Australian nickel:

- Indonesian production cuts restoring price equilibrium

- Carbon tariffs or ESG premiums favouring clean production

- Government subsidies supporting strategic industries

- Technology breakthroughs are reducing processing costs

- Chinese property sector recovery is boosting stainless steel demand

Wyloo maintains it’s studying development of a dedicated nickel concentrator in the Kambalda region, suggesting long-term confidence despite current shutdowns.

Lessons From Six Decades

The Kambalda Nickel Industry story illuminates broader mining truths.

Geological endowment alone doesn’t guarantee success. Policy, technology, and global competition determine winners. First-mover advantages erode. Costs matter more than quality when markets flood with supply.

The discovery that electrified Western Australia in 1966 created genuine prosperity. Thousands of jobs, billions in export revenue, and technical expertise that spread globally. The towns, infrastructure, and processing facilities represent lasting investments.

But commodity mining operates on geological timescales and economic cycles that destroy communities dependent on single resources. Kambalda survived longer than most – six decades from discovery to shutdown exceeds the typical mine life.

The question now isn’t whether nickel exists beneath Kambalda. The Kambalda Dome and Widgiemooltha Dome contain resources that could operate profitably at different price points. The question is whether global markets will reward cleaner, higher-cost Australian production over Indonesian volume.

History suggests patience. Nickel markets have cycled repeatedly since 1966. What differentiates this downturn is Indonesia’s structural cost advantage and production scale.

Yet structural advantages can shift. Environmental regulation, carbon pricing, and supply security concerns create potential paths for Australian nickel’s return. Wyloo’s maintenance of infrastructure and exploration programs indicates companies believe in that possibility.

The Next Chapter

Kambalda’s current silence doesn’t necessarily signal permanent closure.

Mines can restart. Technologies improve. Markets rebalance. The same deposits that produced 1.6 million tonnes of nickel metal over sixty years contain additional resources awaiting economic conditions that justify extraction.

The town endures, supported by nearby gold operations and services for regional mining. Explorers continue probing for the next deposit. Infrastructure remains intact, unlike truly abandoned mining districts.

Sixty years from that momentous January 1966 discovery, Kambalda faces an uncertain but not hopeless future. The Nickel Boom may have ended, but the geology that created it persists.

Whether commodity markets and policy frameworks evolve to support Australian nickel production will determine if Kambalda writes new chapters or becomes a case study in how even great deposits fall victim to global economics.

For now, Australia’s first nickel mine rests, waiting.

Also Read: Global Markets Reel as Wall Street Stumbles and Gold Crashes from Record Highs

FAQ

Q: When was nickel first discovered at Kambalda?

A: Nickel-bearing gossan was first identified in samples from Kambalda in 1954, but the major discovery occurred on 28 January 1966 when Western Mining Corporation intercepted high-grade nickel at 133 metres depth.

Q: Why did Kambalda nickel mines shut down in 2024?

A: Indonesian oversupply caused nickel prices to collapse below US$14,100 per tonne by late 2024, making Australian operations economically unviable. Wyloo Metals placed Kambalda on care and maintenance in May 2024.

Q: How much nickel has Kambalda produced?

A: The Kambalda region has produced over 1.6 million tonnes of nickel metal since 1967, making it one of the most productive nickel districts globally.

Q: Will Kambalda nickel mines reopen?

A: Operations could restart if nickel prices recover to levels that justify Australian production costs. Wyloo Metals maintains infrastructure and continues exploring development options for a new concentrator.

Q: What impact did Indonesia have on Australian nickel?

A: Indonesia’s market share grew from 31.5% in 2020 to 60.2% in 2024, producing cheaper laterite nickel using coal power. This forced multiple Australian operations to close, with national production falling from 150,000 to 60,000 tonnes annually.