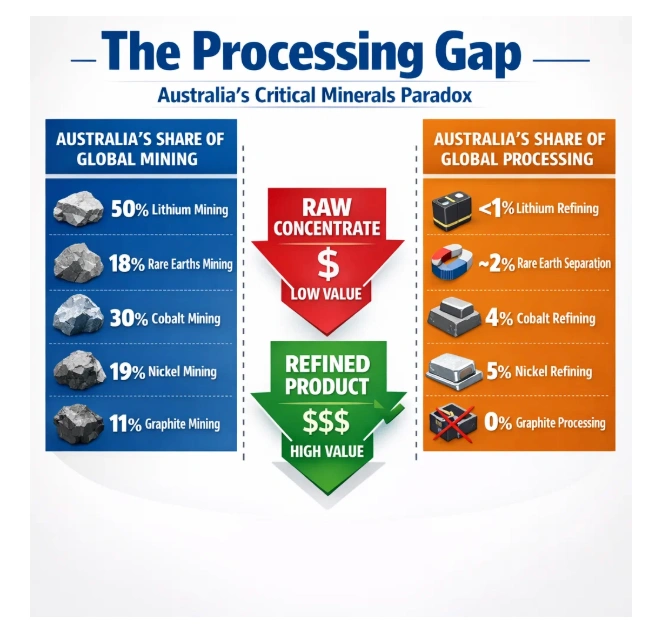

Australia controls more critical mineral reserves than almost any nation on Earth. Yet it processes barely a fraction of what it digs from the ground.

The country produces over half the world’s lithium but refines less than 1 per cent into battery-grade chemicals. It hosts world-class rare earths deposits but relies on Malaysian and Chinese facilities for separation. This paradox defines Australia’s critical minerals dilemma as 2026 approaches.

The gap between geological blessing and industrial reality grows more expensive each year. Raw lithium concentrate sells for perhaps 20 percent of the price commanded by refined lithium hydroxide. Rare earth concentrates fetch far less than separated oxides ready for magnet production. Billions in potential revenue flow offshore annually.

The Processing Bottleneck That Blocks Powerhouse Status

Mining rocks remains Australia’s strength. Turning those rocks into materials the world actually needs? That presents challenges the sector hasn’t solved.

Processing critical minerals demands enormous water volumes and generates substantial waste streams requiring decades of environmental monitoring. These operational realities drive costs far beyond what competitors in less regulated jurisdictions face.

Consider the economics. Australian refineries cost roughly AUD 50,000 per tonne of annual capacity. Chinese facilities cost around AUD 20,000. Construction timelines tell a similar story. China builds lithium refineries in under two years. Australian projects routinely stretch past four years.

Energy expenses compound the disadvantage. Despite abundant renewable resources, Australian industrial power costs exceed what coal-fired Chinese grids charge. Natural gas reduces emissions but drains profit margins.

The processing complexity creates additional hurdles. Rare earth separation requires sophisticated chemical engineering that few companies outside China have mastered. Lynas Rare Earths took more than a decade to develop a commercial-scale heavy rare earth separation capability.

Skills Shortages Slow Progress Across All Fronts

Western Australia’s mining sector already struggles to fill positions. Adding thousands of refinery jobs by 2030 seems optimistic when current operations can’t find workers.

Processing facilities need mechanical engineers, process chemists, and commissioning specialists. These roles require years of specialised training. Universities are expanding materials science programs, but training cycles stretch years, not months.

Skill shortages in critical areas of engineering, drilling and heavy machinery are expected to continue into 2026, with an aging workforce and lack of new entrants widening the generational gap.

The technical knowledge gap runs deeper than staffing numbers suggest. Chinese facilities have decades of institutional knowledge embedded in their operations. Process chemistry for hydroxide extraction requires understanding roasting temperatures, leaching chemistry, and crystal formation that can’t be taught quickly.

Australian companies are starting from scratch in many processing technologies. This disadvantage can’t be overcome without sustained commitment over the years.

Rare Earths Australia: Lynas Leads But Faces Growing Pains

Lynas Rare Earths represents Australia’s most successful critical minerals processing story. The company operates the only significant rare earth separation capacity outside China.

In May 2025, Lynas achieved a breakthrough, becoming the first producer of separated heavy rare earths outside China with the successful production of dysprosium at its Malaysia plant. This strategic capability broke China’s monopoly on heavy rare earth separation.

The achievement wasn’t easy. Power disruptions at the Kalgoorlie processing facility in November 2025 resulted in a significant loss in mixed rare earth carbonate production, creating a potential shortfall equivalent to one month’s production during the quarter.

Infrastructure challenges at home compound operational complexity abroad. Malaysia’s government has repeatedly pressured Lynas over radioactive waste management. The company built a new cracking and leaching facility in Kalgoorlie to address these concerns, but water supply agreements drew community criticism.

Environmental and regulatory hurdles delayed the planned Texas processing facility. Lynas is unlikely to proceed with its plan to build a rare earth processing plant in Texas due to unresolved wastewater disposal permit issues.

Despite these setbacks, Lynas demonstrates that Australian companies can compete in processing. The question remains whether enough others can follow quickly enough to transform the sector.

Government Response: The Strategic Reserve Gambit

Canberra recognises the stakes. The Critical Minerals Strategic Reserve announced in January 2026 commits AUD 1.2 billion to buying and stockpiling domestic production.

The reserve will be operational by the end of 2026, focusing initially on antimony, gallium and rare earths to secure defence and advanced technology supply chains.

The AUD 1 billion allocated for new transactions draws from the expanded AUD 5 billion Critical Minerals Facility. Another AUD 185 million targets strategic mineral stockpiling and implementation costs.

This contract-based approach attempts to address longstanding investment challenges without the fiscal exposure of massive physical stockpiling. The government provides price floor guarantees that reduce project financing risk.

The Critical Minerals Production Tax Incentive adds another layer of support. This 10 per cent production credit on processing and refining costs applies for up to 10 years per project, covering production from 2027-28 through 2039-40.

Whether these measures prove sufficient to overcome Australia’s comparative disadvantages remains uncertain. Chinese operations maintain processing capacity despite operating at financial losses through government support. Competing against subsidised operations forces Australian companies to rely on technological innovation rather than cost competition.

Promising Projects Push Boundaries Despite Obstacles

Several Australian companies are advancing critical minerals projects that could reshape the sector if they reach production.

St George Mining announced a transformative resource estimate for its Araxá Project in Brazil in April 2025. The deposit contains 41.2 million tonnes at 0.68 per cent niobium oxide plus significant rare earth resources. The project benefits from established infrastructure in Brazil’s Minas Gerais mining district.

The company has since expanded exploration through geophysical surveys and diamond drilling campaigns. Araxá’s strategic location adjacent to CBMM’s globally recognised niobium operations provides infrastructure advantages most greenfield projects lack.

Osmond Resources continues advancing its Orion EU Critical Minerals Project in Spain. The project targets rutile, zircon, hafnium, and rare earths across a 12-kilometre east-west corridor.

Recent assay results confirmed mineralised outcrops in all three target zones. Sample results included 8.2 per cent rutile and 4.0 per cent zircon, suggesting robust high-grade zones. The company is now focused on a 15-hole maiden drilling program to validate continuity and grade.

Resolution Minerals received an unsolicited AUD 225 million offer for its Horse Heaven Project in Idaho in August 2025. The antimony-tungsten-gold-silver project benefits from a legacy of supplying critical minerals to the US Government during major conflicts.

The company appointed a US CEO and engaged NASDAQ listing advisors to pursue dual-listing opportunities. These moves align with growing US demand for secure, domestic sources of antimony and tungsten.

Iluka Resources accelerated the development of the Eneabba rare earth refinery in Western Australia. When completed, it will be Australia’s only integrated rare earth separation facility. The project received substantial government support through the Critical Minerals Facility.

Australian critical mineral deposits and mines in 2024 [Geoscience Australia]

What 2026 Must Deliver for Transformation

The next 12 months will determine whether Australia’s critical minerals sector can move beyond aspirational plans to operational reality.

Several key milestones need to be achieved.

Processing facilities must actually get built. The Kalgoorlie rare earth facility needs to ramp to full capacity without further disruptions. Eneabba must progress on schedule. Demonstration plants for new processing technologies require successful commissioning.

Governments are expected to double down on policies addressing geopolitical vulnerabilities through more debt and equity investments, significant commodity pricing interventions and long-term supply contracts.

Workforce development programs must deliver results. Technical training initiatives need to produce qualified process engineers and metallurgists. University partnerships with industry must accelerate knowledge transfer from research to commercial application.

International partnerships require deepening. The US-Australia critical minerals framework, signed in October 2025, committed both nations to invest at least USD 1 billion each within six months. These commitments need follow-through with actual project funding.

Joint investments in projects like Arafura’s Nolans Rare Earths Development aim to stabilise supply chains and attract institutional capital.

Regulatory approvals must accelerate. Projects requiring 3-5 years for environmental approvals can’t compete globally. Streamlined processes that maintain environmental standards while reducing timelines are essential.

Market conditions need cooperation. Commodity volatility, operational costs and skills shortages continue to challenge the industry’s ability to grow and attract investment. Sustained pricing recovery in key minerals would improve project economics significantly.

The China Challenge Remains Central

Any discussion of Australia becoming a critical minerals powerhouse must address the elephant crushing the room.

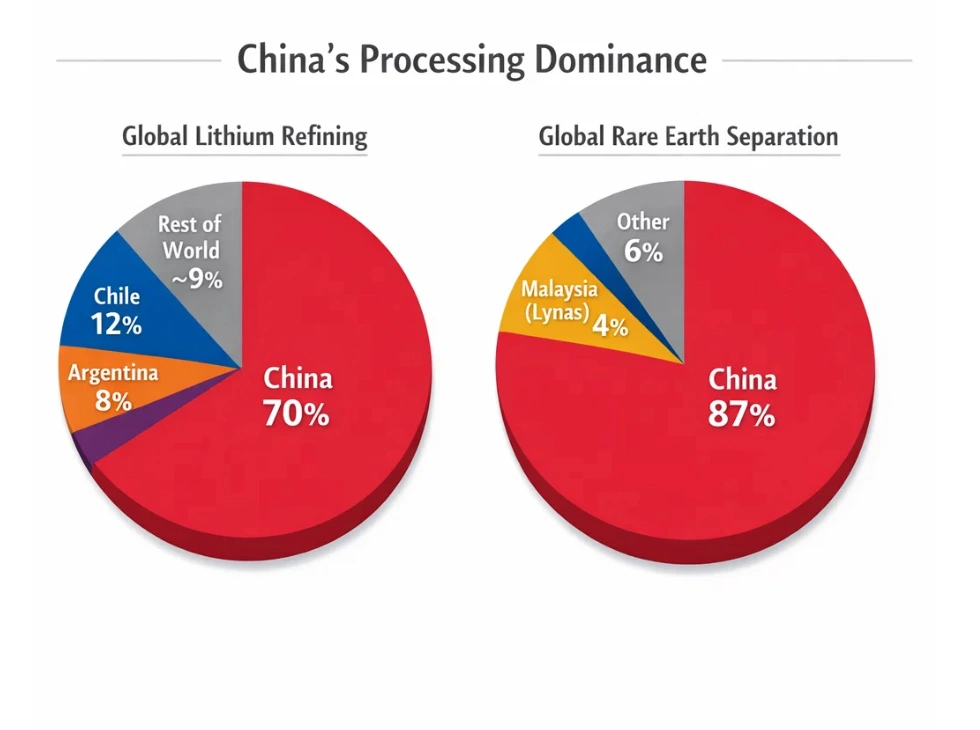

China controls processing not through geological advantage but through decades of strategic investment. The country refines 80 per cent of the world’s rare earths despite producing just 17 per cent of the raw ore. Beijing controls 70 per cent of global lithium refining while producing less than a fifth of mined lithium.

This dominance didn’t happen accidentally. China spent 30 years developing process engineering knowledge, training thousands of chemical engineers, and perfecting production from multiple feedstocks. The country accepts environmental costs competitors can’t and subsidises operations Western shareholders won’t support.

China’s Processing Dominance

Australia’s attempt to build alternative supply chains faces this entrenched advantage. Success requires thinking beyond simple cost competition to strategic value creation.

Focusing on ethical sourcing and ESG compliance offers one differentiation strategy. Western companies increasingly demand transparent, responsible supply chains. Australian producers can command premiums by meeting these requirements.

Developing specialised processing capabilities provides another pathway. Heavy rare earth separation, where Lynas has succeeded, targets high-value, technically challenging materials with tighter supply constraints.

Integrating mining with downstream manufacturing creates a strategic advantage. Projects combining extraction with processing reduce transport costs and enable closer customer relationships.

The Geopolitical Imperative Grows Stronger

Critical minerals have transcended their role as mere commodities. They now function as strategic assets influencing climate policy, defence capability, and geopolitical power.

The transition to electric vehicles alone creates massive demand growth. An EV requires six times the mineral inputs of a conventional vehicle. An offshore wind plant requires nine times more mineral resources than an equivalent gas-fired power plant.

This surge in demand occurs precisely as supply chain concentration creates vulnerability. In the 1990s, major US rare earth mines scaled down or shut their most polluting processing activities, and China ultimately absorbed much of this capacity.

Western governments now recognise this dependency as unacceptable. The US Department of Defence funds rare earth projects specifically to diversify supply chains. European Union frameworks target 10 per cent consumption coverage from strategic projects by 2030.

Australia’s stable political system, developed infrastructure, and skilled workforce position it advantageously in this environment. The country offers what China-dependent supply chains lack: reliability, transparency, and alignment with democratic values.

Whether Australia capitalises on these advantages depends on execution over the next few years.

The Verdict: Potential Meets Reality in 2026

Australia possesses everything needed to become a critical minerals superpower except one thing: the willingness to pay the price required to get there.

The geological resources exist. The political stability attracts investment. The strategic alignment with Western partners creates demand. What’s missing is the sustained, multi-decade commitment to build processing capabilities that can compete with Chinese efficiency.

2026 represents an inflection point. The Strategic Reserve demonstrates government commitment. The US partnership opens markets. Technology developments at pilot plants show promise. Projects like St George’s Araxá and Osmond’s Orion advance toward production.

But recognition and ambition don’t equal achievement. Chinese facilities took decades to develop current capabilities. Australian operations can’t replicate that institutional knowledge overnight, regardless of funding.

The question isn’t whether Australia can become a critical minerals powerhouse. The geology guarantees it could. The question is whether the country will commit to the long, expensive journey required to make a potential reality.

2026 will begin answering that question. Actual facilities getting built, workers getting trained, and minerals getting processed will matter more than any policy announcement or government fund.

Australia’s path to critical minerals leadership won’t be quick or easy. But the alternative, remaining a quarry for other nations’ manufacturing, grows more costly each year both economically and strategically.

The resources underneath the continent aren’t going anywhere. Whether Australia captures the value they represent depends on the choices made over the next 12 months and the years that follow.

Also Read: 2026 Rankings Reveal Winners and Losers in Global Travel Freedom

FAQs: Australia’s Critical Minerals Sector

Q: Why does Australia have low critical minerals processing capacity despite abundant resources?

A: High construction costs, lengthy approval timelines, energy expenses, and workforce shortages make Australian processing facilities less competitive than Chinese alternatives. Environmental regulations that prevent shortcuts increase costs further.

Q: Which companies are leading Australia’s critical minerals development?

A: Lynas Rare Earths operates the largest rare earth processing outside China. St George Mining, Osmond Resources, and Resolution Minerals are advancing significant projects. Pilbara Minerals and IGO Limited lead lithium production.

Q: What role does the government play in developing the sector?

A: The AUD 1.2 billion Strategic Reserve, AUD 5 billion Critical Minerals Facility, and 10 per cent production tax incentive aim to de-risk projects and attract investment. International partnerships with the US and allied nations provide additional support.

Q: How long will it take for Australia to become a processing powerhouse?

A: Industry experts estimate 5-10 years for significant processing capacity development, depending on sustained government investment and technological advancement success. Some projects could reach production sooner, but large-scale transformation requires a decade minimum.

Q: What threatens Australia’s critical minerals ambitions?

A: Commodity price volatility, Chinese market manipulation, skills shortages, capital intensity requirements, and regulatory complexity all present obstacles. Climate between nations and geopolitical tensions add further uncertainty.