Researchers at Stanford Linear Accelerator Centre have upended conventional wisdom about gold’s chemical nature. The team led by Mungo Frost accidentally created gold hydride during a high-pressure laboratory experiment. This discovery fundamentally altered our understanding of how gold behaves under extreme conditions.

Scientists squeezed hydrogen atoms into gold foil using pressures hundreds of thousands of times Earth’s atmosphere. The experiment reached temperatures exceeding 3,500 degrees Fahrenheit. Under these extraordinary conditions, gold revealed an unexpected capacity for chemical reactivity. The team discovered the first confirmed solid compound composed exclusively of gold and hydrogen atoms ever produced in laboratory settings.

Gold revealed an unexpected capacity for chemical reactivity

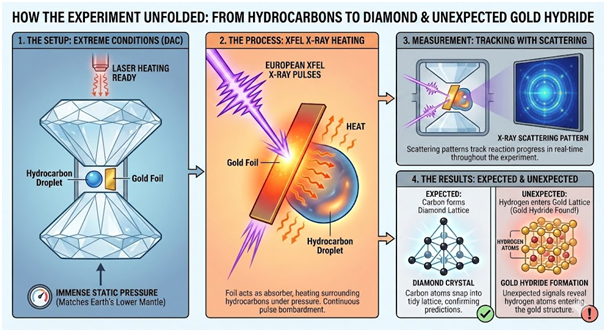

How the Experiment Unfolded

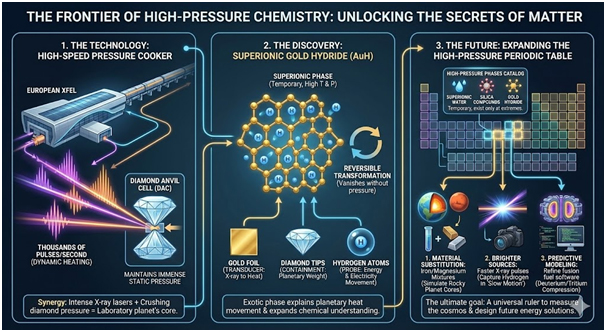

The original research aimed to study how hydrocarbons transform into diamond under crushing pressure and intense heat. Researchers positioned tiny hydrocarbon droplets between diamond anvil cell tips. This device traps samples at immense static pressures whilst allowing laser heating. The European XFEL facility in Germany supplied powerful X-ray pulses to the thin gold foil.

The gold foil functioned as an X-ray absorber, heating the surrounding hydrocarbons beneath the intense laser bombardment. Scientists gradually increased pressure until it matched Earth’s lower mantle conditions. Multiple trains of X-ray pulses then bombarded the sample continuously. The measurement process employed X-ray scattering patterns to track the reaction progress throughout the experiment.

Carbon atoms snapped into the tidy lattice of diamond, confirming the researchers’ earlier predictions. However, unexpected signals revealed hydrogen atoms entering the gold lattice structure. This observation marked the moment gold hydride formation became apparent to the research team.

Experiment explained

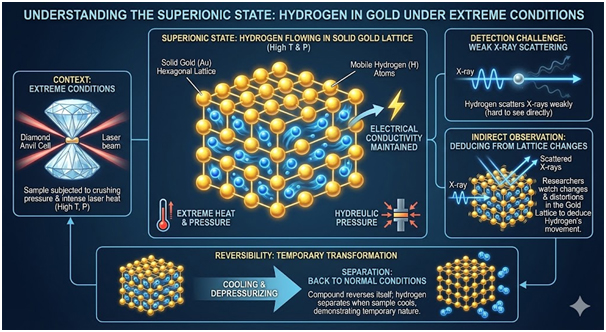

Understanding Superionic States and Hydrogen Behaviour

Under extreme pressure and heat, hydrogen entered a superionic state within the gold compound. This state allows atoms to move like liquid inside solid structures. The hydrogen atoms maintained electrical conductivity throughout the gold hydride material. Hydrogen typically scatters X-rays very weakly, making direct observation challenging.

The researchers watched changes in the gold lattice to deduce how the light atoms moved through it. Simulations and measurements indicated that hydrogen diffuses rapidly through the hexagonal gold lattice at high temperatures. However, hydrogen separated from gold when the sample cooled back to normal conditions. The compound essentially reversed itself, demonstrating the temporary nature of this exotic phase.

Understanding the superionic states

Implications for Planetary Science and Fusion Research

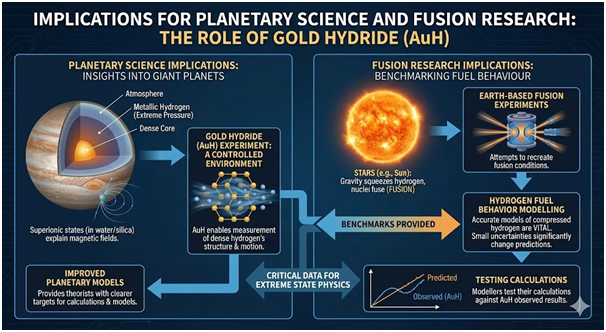

Interior models of Jupiter suggest metallic hydrogen surrounds a dense core beneath crushing pressures. These environments experience pressures far beyond anything found on Earth’s surface. Recent research demonstrated that superionic states in water and silica hydrogen mixtures explain magnetic fields in giant planets. Gold hydride offers a controlled environment where scientists can measure dense hydrogen’s structure and motion.

This knowledge provides theorists with clearer targets for planetary calculations and models. Stars like the Sun shine because gravity squeezes hydrogen until nuclei fuse together. Fusion researchers attempt to recreate these conditions in experiments conducted on Earth. Accurate models of hydrogen compressed to extraordinary pressures and densities prove vital for understanding fusion fuel behaviour.

Simulations indicate that even small uncertainties in hydrogen behaviour at high density significantly change fusion predictions. By pinning how hydrogen moves through gold at given pressures and temperatures, measurements provide fusion modellers with benchmarks. The team can test their calculations against these observed results.

Implications for Planetary Science and Fusion Research

Redefining Gold’s Chemical Properties

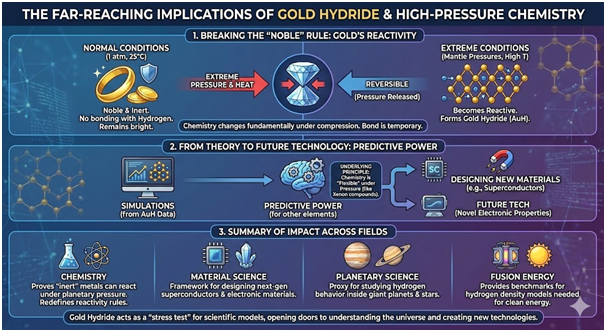

In everyday chemistry, gold belongs with noble metals that rarely form compounds with other elements. This quality explains why jewellery remains bright and unblemished for decades. Gold formed a hydride that held more hydrogen as pressure climbed progressively. However, the compound separated into plain gold again when conditions returned to normal.

The findings reveal that extreme pressure and heat enable chemistry forms that do not occur under normal conditions. High pressure work previously demonstrated unreactive elements like xenon can form compounds. Gold hydride underscores how chemistry fundamentally changes when matter undergoes compression. Other metals already display properties like superconductivity in their hydride forms.

Understanding gold hydride could eventually help researchers design new electronic materials for future technologies. The simulation framework that captured superionic hydrogen in gold can predict how other elements behave. Scientists can test whether strange hydrides emerge when infusing elements with hydrogen at different pressures and temperatures.

Implications of Gold Hydride

Future Research Directions and Discoveries

Future experiments can substitute gold for other metals or mixtures resembling planetary materials more closely. Each compound uncovered at such extremes expands the periodic table of high-pressure phases considerably. These discoveries clarify how ordinary elements behave when subjected to extraordinary conditions. Tougher diamond anvils and brighter X-ray sources continuously improve research capabilities.

The European XFEL facility delivers thousands of pulses per second to sample targets. These pulses deposit energy in the gold foil, allowing rapid sample heating. The diamond-anvil cell maintains pressure throughout the entire heating process. High-energy-density science combines intense X-ray lasers with diamond anvil cells for unprecedented material investigation.

Gold hydride joins a catalogue of exotic phases including superionic water and silica compounds. These phases appear only when atoms undergo compression and heating together. Most vanish once pressure or temperature drops, yet their existence explains planetary heat movement. The study expands scientific understanding of chemical behaviour at conditions once considered purely theoretical.

Future Research Directions and Discoveries