The great Australian dream of home ownership is slipping away. Not gradually, but violently.

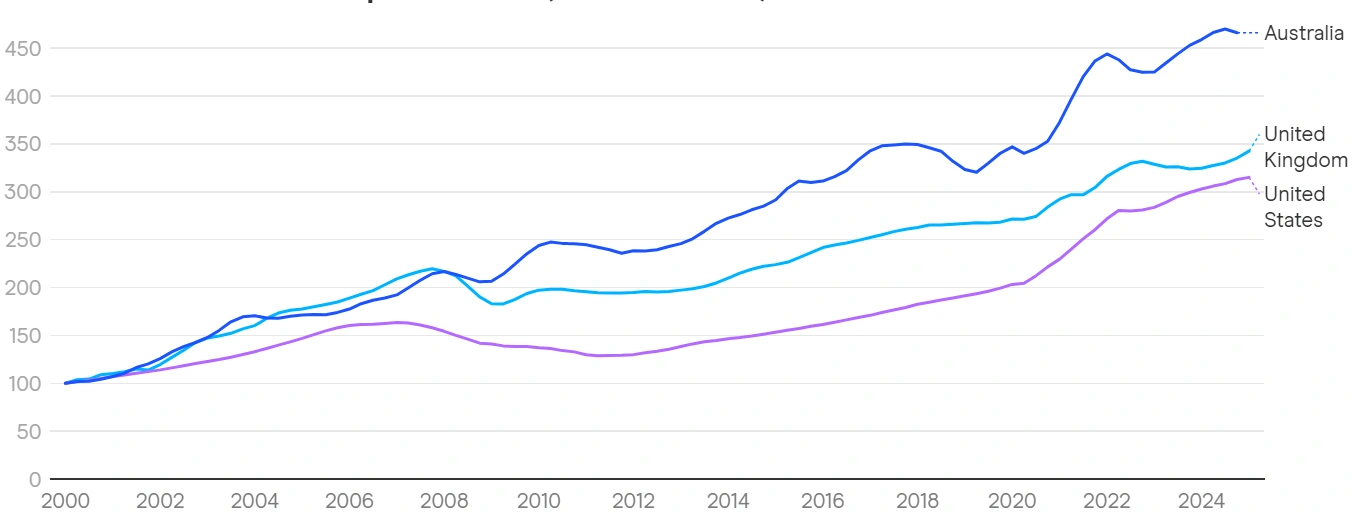

Young Australians today face a housing market that defies logic, fairness, and economic sense. Prices have surged 44% in five years while wages crawled ahead at a fraction of that pace. The result? A crisis that threatens the social fabric of the nation.

The Numbers Don’t Lie

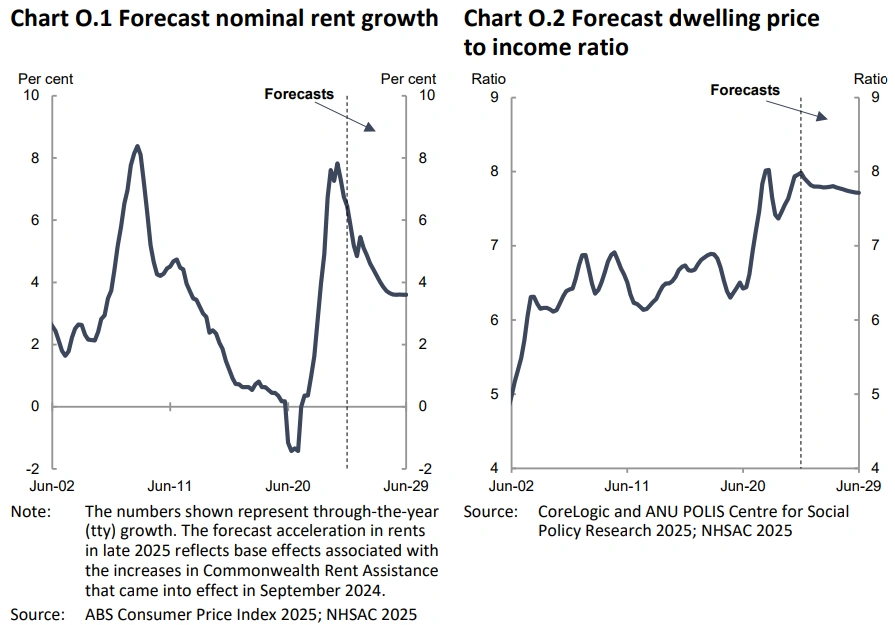

The Australian housing crisis has reached a breaking point. Home values jumped 4.9% in 2024 alone, pushing the median dwelling price to $831,000 by mid-2025. Rents climbed 4.8% over the same period, adding nearly $10,500 to annual rental bills since 2020.

Meanwhile, household incomes rose just 4.3% in the year to September 2024. The gap between what people earn and what homes cost keeps widening.

The National Housing Supply and Affordability Council delivered a stark warning in May 2025. Australia will fall 375,000 homes short of its target to build 1.2 million new dwellings by mid-2029. When you factor in demolitions, the net shortfall balloons even further.

Forecast nominal rent growth and the dwelling price to income ratio

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz, Chair of the Council, minced no words: “Australia is still very much in a housing crisis that has been decades in the making.”

First Home Buyers: Caught in the Crossfire

First home buyers aren’t just struggling anymore. They’re desperate.

A Finder report released in June 2025 revealed troubling statistics:

- 65% of first home buyers are already in mortgage stress or expect to be

- 45% regret their purchase decision within the first year

- 38% bought purely out of fear that prices would become unaffordable

- 70% purchased with less than a 20% deposit

The average deposit now sits at $159,000, a staggering 50% jump from 2020. For a median-income household, saving that amount takes more than a decade.

Jenni Shaw, a 28-year-old marketing professional in Sydney, represents the new normal. She and her partner spent three years aggressively saving, skipping holidays and eating at home every night. They still needed help from both sets of parents to scrape together enough for a 10% deposit on a modest unit 40 kilometres from the CBD.

“We paid $80,000 more than we budgeted,” Shaw says. “But we had to. If we waited another year, we’d be priced out forever.”

That’s the psychology driving today’s market. Not aspiration, but panic.

Nominal national house price index (2000 to 2025)

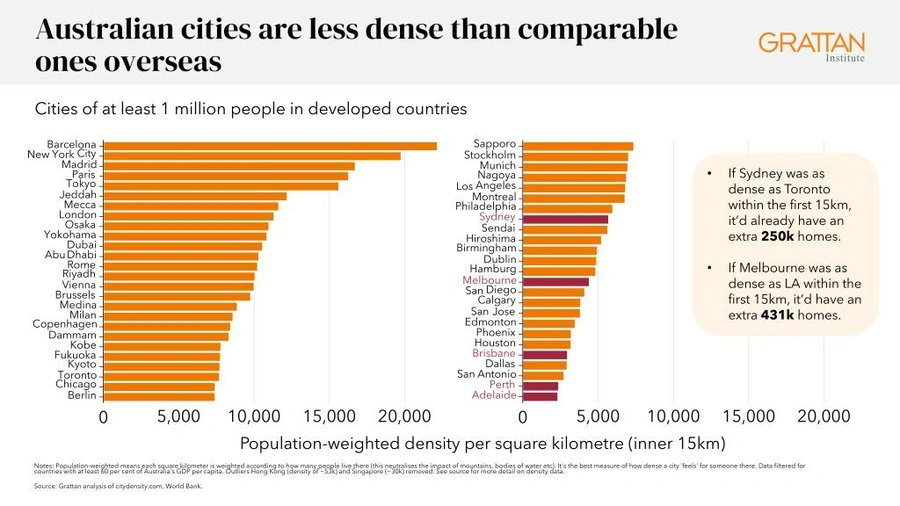

The Grattan Solution: Build Up, Not Out

The Grattan Institute’s November 2025 report offers a radical but necessary prescription. The think tank argues Australia’s planning systems actively prevent the construction of housing where people want to live.

The data is damning:

- 80% of residential land within 30km of Sydney’s centre is zoned for three storeys or fewer

- 87% of Melbourne’s residential land faces the same restriction

- Brisbane, Perth, and Adelaide have even tighter controls

These restrictions add hundreds of thousands of dollars to new housing costs. They force people to move further from jobs, schools, and transport. They create longer commutes, higher emissions, and lower quality of life.

Grattan’s proposal is straightforward. Allow three-storey townhouses and apartments on all residential land in capital cities. Permit buildings of six storeys or more around transit hubs and commercial centres. Make approvals automatic for developments meeting clear standards.

The modelling shows these reforms could:

- Boost housing construction by 67,000 homes annually

- Cut rents by 12% over a decade

- Reduce median home prices by more than $100,000

- Create capacity for one million new homes in Sydney alone

Grattan Institute’s November 2025 report

Government Schemes: Help or Hindrance?

The federal government’s expanded First Home Guarantee scheme came into effect in October 2025, allowing all first home buyers to purchase with just a 5% deposit. The government acts as guarantor for the remainder, eliminating costly Lenders Mortgage Insurance.

Sounds helpful, right?

Economists aren’t convinced. Sally Tindall from Canstar warned the scheme would “add demand into a red-hot property market.” Ben Phillips from the Australian National University questioned Treasury’s claim that the scheme would only lift prices by 0.5% over six years.

The Parliamentary Library crunched the numbers. A nurse earning $2,011 weekly before tax would need to spend 76% of income on mortgage repayments for an average Sydney house under a 95% loan. That’s not homeownership. That’s indentured servitude.

Buyers taking out 95% loans instead of 80% loans pay an extra $133,000 in interest over the life of the mortgage, according to CoreLogic estimates. The government subsidy looks generous upfront but locks people into decades of higher costs.

Where First Home Buyers Are Actually Buying

Faced with impossible prices in capital cities, first home buyers are adapting. A quarter are now searching for properties in different regions or states.

The pattern is clear across Australia:

- Sydney buyers head west to Penrith and Campbelltown

- Melbourne buyers push north-west to Melton and Wyndham

- Brisbane buyers target northern growth corridors

- Perth’s south-east draws first-timers with relative affordability

- Adelaide’s northern suburbs remain hotspots

Regional centres like Geelong, the Central Coast, and areas within two hours of capital cities are seeing surging demand. Median house prices in capital cities sit 48% higher than regional areas, creating a powerful price incentive to move further out.

The trade-off? Longer commutes, fewer job opportunities, and less access to services and amenities. First home buyers aren’t choosing these locations because they prefer them. They’re choosing them because they have no other option.

The Bank of Mum and Dad

Family assistance has become essential rather than exceptional. In 2025, 17% of first home buyers received money from parents, up from 11% in 2022.

The impact is stark. Buyers with family support took an average of just over three years to save a deposit. Those without support needed five years or more. The assisted buyers also had 41% more savings remaining after purchase.

This creates a two-tiered system. Those born into wealth can enter the market sooner, build equity faster, and secure financial stability. Those without family resources fall further behind with each passing year.

Home ownership, once the great equaliser in Australian society, now entrenches existing privilege.

What Happens Next?

The Reserve Bank began cutting interest rates in February 2025, with further cuts expected through 2026. Lower rates will boost borrowing capacity and make repayments more manageable in the short term.

But rates aren’t the root problem. Supply is.

Australia had the lowest housing stock per capita in the developed world before COVID-19, with approximately 400 homes per 1,000 people. The construction industry fell 65,970 homes (27%) short of government targets in 2024-25. Meanwhile, net overseas migration has surged back to record highs, adding 205,000 new households in 2024-25 alone.

The maths is brutal. Demand keeps rising. Supply keeps falling short. Prices keep climbing.

Without fundamental planning reform, government incentives and rate cuts will merely shift demand around rather than solve the underlying shortage. They’ll help some buyers enter the market while pushing prices higher for everyone else.

The Path Forward

Housing experts agree on the necessary steps:

- Comprehensive planning reform to allow denser development

- Massive investment in social and affordable housing

- Infrastructure spending to support growth areas

- Construction industry reforms to boost productivity

- Tax system changes to prioritise supply over speculation

The political will remains absent. State governments rely heavily on stamp duty revenue, making them reluctant to embrace land tax reform. Existing homeowners resist density increases in their suburbs, fearing impacts on property values and neighbourhood character.

Neither major party has shown appetite for the transformational change required. Both propose incremental adjustments that tinker at the edges while the core problems intensify.

Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz summarised the challenge: “This is a crisis that took decades to create, and it’s going to take decades to fix, but we do need someone to step up and take the first steps.”

Also Read: A Final Promise Kept: Graham Richardson’s Last Act of Love Before Passing at 76

The Human Cost

Behind every statistic sits a person whose life has been diminished by this crisis. The couple postponing children because they can’t afford a bigger home. The skilled worker leaving Australia for countries with saner housing markets. The retiree forced to keep working because rising rent consumed their savings.

Mary, a 59-year-old former postal worker in regional New South Wales, has spent two years bouncing between short-term accommodations with her daughter and dog. She receives $836.50 fortnightly in unemployment assistance but can’t afford the median $560 weekly rent. The social housing waitlist is “very, very long,” she was told.

This is Australia in 2025. A wealthy, developed nation unable to provide its citizens with affordable shelter.

The Australian housing crisis isn’t an economic problem that can be solved with spreadsheets and policy tweaks. It’s a moral failure that demands urgent action.

Without it, home ownership will become the exclusive preserve of the wealthy and the well-connected. The great Australian dream will remain just that: a dream, fading further from reach with each passing year.