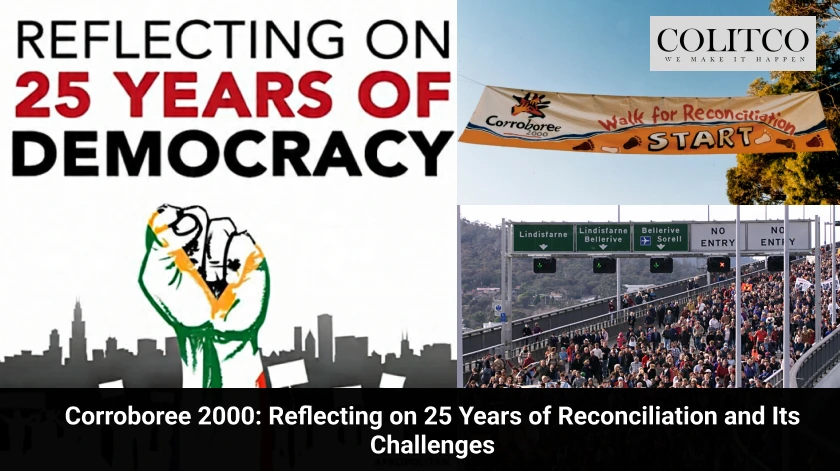

On a cold day 25 years ago, 250,000 people marched across Sydney Harbour Bridge for Indigenous reconciliation. The event, known as Corroboree 2000, symbolised a nationwide push for unity. It took more than six hours for the crowd to cross from north to south, reflecting a shared hope to overcome Australia’s difficult past with its First Nations people. Across the country, smaller bridge walks echoed the same message of reconciliation and coming together.

The Decade of Reconciliation

The march followed the 1991 Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation Act, which marked the start of a “Decade of Reconciliation.” This act committed the federal government to address both Aboriginal disadvantage and aspirations by 2001, the centenary of Federation. However, the act did not define reconciliation or set clear goals, which left the target ambiguous. The lack of clarity allowed political parties to interpret reconciliation differently, focusing either on rights or disadvantage. Some First Nations activists criticised reconciliation as a poor substitute for Treaty and land rights. Uncle Chicka Dixon labelled the movement “ReCONsillynation,” suggesting it called to “walk together” instead of pursuing Treaty and land rights.

Building Knowledge and Understanding

The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation aimed to educate non-Indigenous Australians about Indigenous lives, history, and culture. It recruited thousands of participants and produced educational materials to promote learning. Community-led reconciliation activities grew, establishing a foundation for truth-telling and awareness. At the same time, major events changed the landscape. The 1992 Mabo decision overturned the doctrine of terra nullius, leading to native title laws that allowed some Indigenous people to claim traditional land ownership. The 1997 Bringing Them Home report exposed the trauma caused by the forced removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children, known as the Stolen Generations. The report recommended official apologies from all governments. By 1999, all states and territories had apologised, but the federal government had not.

Political Divisions and Historical Debate

The 1990s saw political leaders take contrasting positions on history. Labor Prime Minister Paul Keating sought to create a new national story by highlighting colonisation’s impact on Aboriginal people. Keating combined native title with republicanism to challenge the Anglo-centric national narrative. Liberal leader John Howard rejected this, encouraging Australians to “feel comfortable and relaxed about their history.” Howard accused Labor of promoting the “black armband” view of history and avoided apologising for past wrongs. Instead, he emphasised “practical outcomes” over symbolism but failed to deliver on both.

Also Read: Klarna’s Rising Losses Raise Questions: Is Buy Now, Pay Later In Trouble?

Corroboree 2000 and Its Outcomes

Corroboree 2000 took place over two days in May, with Indigenous and non-Indigenous leaders meeting at the Sydney Opera House. The Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation presented two documents: the Australian Declaration Towards Reconciliation and the Roadmap for Reconciliation. Leaders left their handprints on a canvas to show support. The event’s spirit was influenced by the Howard government’s focus on practical reconciliation, which emphasised overcoming disadvantage over addressing Indigenous aspirations. Howard expressed “regret” for past treatment but did not apologise, leaving many disappointed. The formal apology would come later, in 2008, from Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

Current Perspectives on Reconciliation

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese recently emphasised national unity and placed reconciliation at the centre of his Indigenous affairs agenda. He stated the government will support reconciliation to become a stronger nation by closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. This stands in contrast to his 2022 promise to fully implement the Uluru Statement from the Heart. After the Voice referendum, Albanese’s government prioritises First Nations economic independence, empowerment, and closing the gap in disadvantage. Reconciliation remains a key part of government policy, responding to First Peoples’ calls for justice and recognition. However, reconciliation can also act as a safe harbour, where more ambitious Indigenous agendas stall or fail.

A Continuing Journey

The legacy of Corroboree 2000 is complex. It represents a significant moment of national reflection and hope. Yet, reconciliation’s meaning and impact continue to evolve amid political debates and social challenges. The march symbolised unity, but the journey towards justice and equality for Indigenous Australians remains ongoing. As Australia marks 25 years since the event, it faces both the successes and limitations of reconciliation in shaping its future.