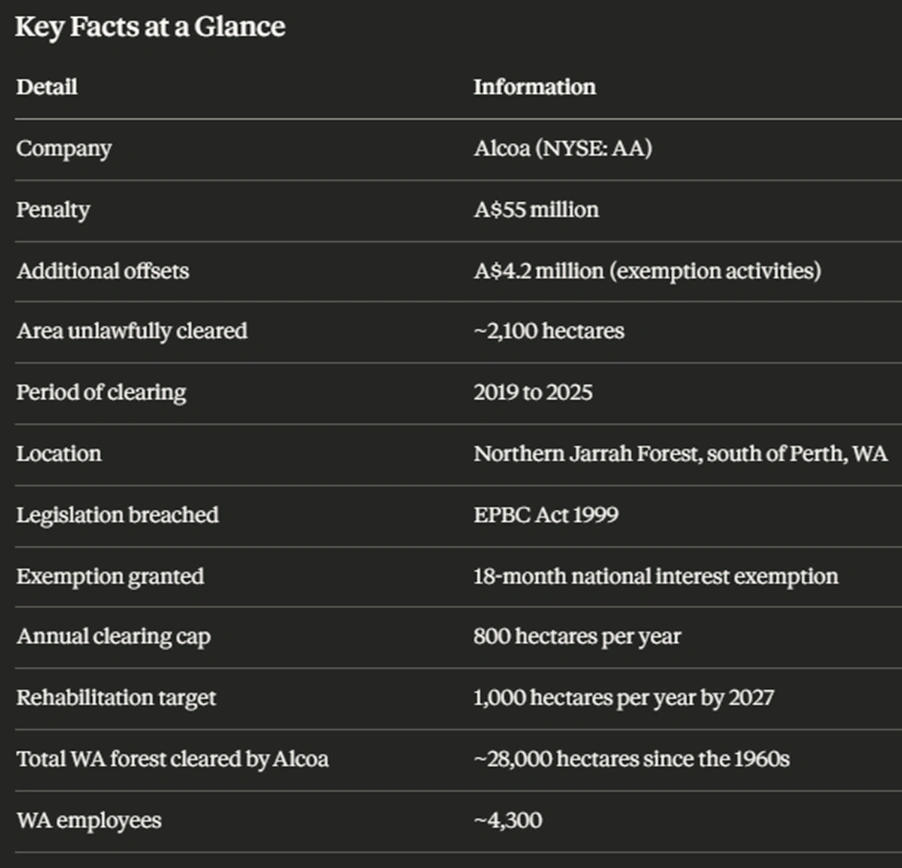

Alcoa, the US aluminium giant, has agreed to pay A$55 million to the Australian federal government after unlawfully clearing nearly 2,100 hectares of the protected Northern Jarrah Forest in Western Australia without the required approvals. The settlement, reached on 18 February 2026, is the largest conservation-focused enforcement action of its kind in Australian history.

The clearing took place over six years, between 2019 and 2025, as the company mined bauxite beneath one of the world’s most biodiverse temperate forests, south of Perth. Alcoa did not seek approvals under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) before proceeding.

Federal Environment Minister Murray Watt described the agreement as unprecedented, saying it set a new benchmark for corporate accountability in the Australian mining sector.

Key facts summary for Alcoa’s enforcement action in Western Australia

What the $55 Million Settlement Covers

The A$55 million payment funds a range of conservation commitments enforced through a legally binding undertaking with the Federal Court. The settlement includes:

- Permanent ecological offsets to preserve critical habitat within the Northern Jarrah Forest

- Expanded conservation programs for Western Australia’s three black cockatoo species, which nest in jarrah trees and are listed as threatened under Australian law

- Strengthened invasive species management across the forest

- An additional A$4.2 million in environmental offsets for activities permitted under an 18-month national interest exemption

The black cockatoos are central to the ecological fabric of the Northern Jarrah Forest. Their survival depends directly on old hollow-bearing trees, many of which were destroyed by Alcoa’s unapproved clearing operations.

Alcoa Gets a Green Light to Keep Clearing, For Now

Despite receiving Australia’s largest environmental penalty of this type, Alcoa has simultaneously been granted a national interest exemption by Minister Watt. This allows the company to continue limited land clearing for 18 months while a broader strategic assessment of its operations is completed.

The exemption reflects the economic weight Alcoa carries in Western Australia. The company employs around 6,000 workers across Australia, with approximately 4,300 based in the state. It has mined bauxite from WA forests since the 1960s, clearing roughly 28,000 hectares of native jarrah forest in total.

Alcoa has committed to capping annual clearing at 800 hectares and ramping up rehabilitation rates to 1,000 hectares per year by 2027. The strategic assessment will evaluate cumulative environmental impacts of the company’s operations through to 2045.

“This agreement will enable the government to assess the cumulative environmental impacts of Alcoa’s local mining operations and provide strong protections for threatened species and ecological communities, while offering Alcoa long-term operational certainty,” Minister Watt said.

Alcoa’s Response

Alcoa’s president and chief executive, William F Oplinger, said the company welcomed the move toward modernising its approvals framework and remained committed to responsible operations.

The company maintained it had generally operated within Australia’s legal framework while acknowledging its historical clearing activity. The settlement is structured as an enforceable undertaking rather than a criminal penalty, meaning Alcoa avoids formal prosecution by meeting its obligations.

The Minerals Council of Australia backed the resolution, with chief executive Tania Constable calling it a pragmatic decision and urging governments to fast-track national environmental standards to reduce mine approval delays.

Community Backlash Has Been Building for Years

The Alcoa fine did not arrive without warning. Community resistance to the company’s expansion plans has grown sharply in recent years.

Alcoa’s proposal to clear an additional 11,500 hectares drew a record-breaking 59,000 public submissions to the Environmental Authority. Local governments in the Peel and South West regions, along with multiple First Nations representatives, were vocal critics. Botanists and ecologists have also challenged the effectiveness of Alcoa’s rehabilitation programs, with a prominent researcher who previously worked alongside the company publicly disputing whether its restoration efforts adequately replace what is destroyed.

The Northern Jarrah Forest is the only forest of its type on Earth. It hosts rare marsupials, ancient plant species, and threatened birds. Any clearing is ecologically sensitive by definition.

An aerial view of Alcoa’s Huntly Mine site within Western Australia’s Northern Jarrah Forest, where nearly 2,100 hectares were cleared without federal approval between 2019 and 2025. [Conservation Council of WA]

You can read more about how mining intersects with sustainability pressures in Australia and how the sector balances extraction with environmental responsibility.

The Broader Stakes: Environmental Law and Mining in Australia

The Alcoa case raises serious questions about compliance culture within the mining industry. Clearing 2,100 hectares without EPBC Act approvals over six years is not a paperwork oversight. Modern satellite monitoring systems can detect vegetation clearing at fine resolution, and regulatory enforcement is growing more sophisticated.

As Colitco has previously reported, eco-concerns around bauxite mining in Australia’s northern jarrah forests have been documented since at least 2022, when conservation groups released detailed data on fragmented habitat across the Darling Range.

The case also sets a financial precedent. With individual corporate violations under Australian law capable of attracting penalties of up to A$11.1 million per contravention, enforcement actions that aggregate multiple violations across large affected areas can quickly multiply into figures that force even major multinationals to reckon with non-compliance.