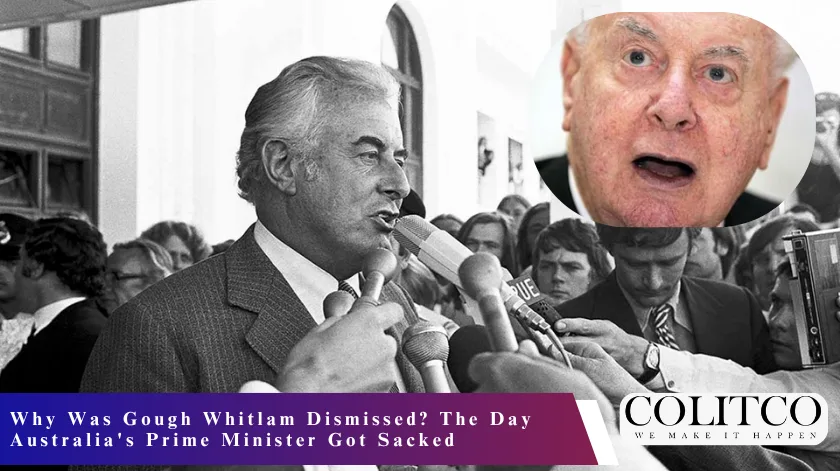

On November 11, 1975, Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed Gough Whitlam, Australia’s 21st prime minister, in the most dramatic political crisis the nation has ever witnessed. The Gough Whitlam dismissal remains controversial five decades later, raising fundamental questions about democracy, constitutional power, and who truly governs Australia.

Whitlam arrived at Government House that Tuesday morning expecting routine approval for a half-Senate election. Instead, he received a letter terminating his employment as prime minister. Within hours, Opposition leader Malcolm Fraser was sworn in as caretaker prime minister, budget bills rushed through the Senate, and parliament dissolved.

The speed shocked everyone. The consequences still reverberate today.

Who Was Gough Whitlam?

Edward Gough Whitlam (1916-2014) served as Australia’s 21st prime minister from December 1972 to November 1975. He remains the only Australian prime minister ever dismissed by a Governor-General.

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 1916 – 21 October 2014), 21st prime minister of Australia

Whitlam was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1952 for the western Sydney seat of Werriwa. He became Labor leader in 1967 and rebuilt the party after decades in opposition.

His government transformed Australian society. From healthcare to education, from foreign policy to social justice, Whitlam’s reforms created the modern Australia we know today.

He continued in parliament until 1978, then served as Ambassador to UNESCO in Paris. Whitlam remained politically active into his 90s, dying in October 2014 at age 98.

He never forgave Kerr. As late as 2005, Whitlam called him a “contemptible person.”

What Led to Gough Whitlam’s Dismissal?

The Gough Whitlam dismissal didn’t happen in isolation. It was the culmination of weeks of constitutional warfare between the Labor government and the Liberal-National Coalition opposition.

The Supply Crisis

Fraser’s Coalition controlled the Senate. In October 1975, they refused to pass budget appropriation bills that had already cleared the House of Representatives. No budget meant no money for public servants, essential services, or government operations.

Fraser demanded Whitlam call an election. Whitlam refused, arguing he held a clear majority in the House of Representatives where governments are properly formed.

The standoff paralysed Canberra. Each side believed constitutional convention supported their position. Both were partly right.

The Loans Affair Scandal

The crisis had deeper roots in the “Loans Affair” of late 1974. Treasurer Jim Cairns and Minerals Minister Rex Connor attempted to secretly borrow $4 billion from Middle Eastern sources, bypassing traditional channels and constitutional protocols.

When revealed, the scandal devastated public confidence. Whitlam eventually dismissed both ministers, but the damage was done. The Coalition smelled blood.

Twenty-Three Years of Waiting

To understand why the Gough Whitlam dismissal happened, you need context. The Australian Labor Party had been locked out of power for 23 years before Whitlam’s 1972 victory. When Labor finally won, they governed like it might be their only chance.

In less than three years, Whitlam’s government enacted 508 bills:

- Established Medibank (now Medicare) for universal healthcare

- Abolished university fees and conscription

- Ended Australia’s involvement in Vietnam

- Dismantled the White Australia Policy

- Advanced Indigenous land rights

- Recognised China diplomatically

The reform pace was breathtaking. The political backlash was inevitable.

How Did the Dismissal Actually Happen?

The morning of November 11, 1975, Whitlam sought Kerr’s approval for a half-Senate election to break the deadlock. It seemed like a reasonable compromise.

Kerr had spent weeks consulting with Chief Justice Sir Garfield Barwick about using his constitutional “reserve powers” to dismiss the government. Recent archival discoveries reveal he also corresponded with Queen Elizabeth II’s private secretary about his plans.

The Moment of Dismissal

When Whitlam arrived at Government House, Kerr handed him a letter. The Prime Minister of Australia was fired, effective immediately. No warning. No consultation with cabinet. No opportunity to test the matter in parliament.

Kerr then appointed Fraser as caretaker prime minister on one condition: pass the supply bills immediately and call a double dissolution election.

Fraser rushed to Parliament House. Before most Labor MPs even knew what had happened, Coalition senators voted through the budget bills. Kerr signed the proclamation dissolving parliament.

By mid-afternoon, it was done. Three years of Labor government ended in three hours.

Whitlam’s Famous Speech

On the steps of Parliament House, with television cameras rolling, Whitlam delivered his response:

“Well may we say ‘God save the Queen’, because nothing will save the Governor-General.”

The crowd chanted “We want Gough!” David Smith, the Governor-General’s official secretary, could barely be heard reading the dissolution proclamation over the noise.

Journalist Bob Wilesmith captured the moment on film. That footage has defined the Gough Whitlam dismissal in Australian political consciousness ever since.

Was the Gough Whitlam Dismissal Constitutional?

This question has divided Australian democracy for 50 years. The answer depends on which constitutional principles you prioritise.

The Case For Dismissal

Section 64 of the Australian Constitution grants the Governor-General power to appoint and dismiss ministers. These “reserve powers” exist for extraordinary circumstances.

Kerr argued that a government unable to secure supply cannot govern. Constitutional convention, he believed, required Whitlam to either resign or advise an election.

The High Court never ruled on whether Kerr’s actions were constitutional. It didn’t need to – the electorate delivered their verdict at the ballot box.

The Case Against Dismissal

Whitlam held a clear majority in the House of Representatives. Under responsible government principles inherited from Britain, that’s where governments are tested.

The Senate’s power to block supply, Whitlam argued, should not extend to toppling elected governments. Kerr could have waited for the House to pass a motion of no confidence (which would have failed) before acting.

Critics note Kerr sought advice from Barwick, who had strong Liberal Party connections. He also corresponded with the Queen’s office despite later claims of acting independently.

Recent archival revelations from Canada confirm Kerr discussed the dismissal with royal officials beforehand. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, marking the 50th anniversary, called it “not a constitutional crisis – it was a partisan political ambush.”

What Happened After the Dismissal?

Fraser’s caretaker government faced voters on December 13, 1975. The result was crushing for Labor.

The Coalition won the largest majority in Australian parliamentary history. Whitlam lost 30 seats in the House of Representatives. The Senate swung decisively to the conservatives.

The electorate’s verdict was clear: however questionable the dismissal’s legality, they didn’t want Whitlam’s government back.

Fraser governed until 1983. Kerr resigned as Governor-General in 1977, spending his final years largely in exile. When he died in 1991, few attended his funeral, and his death wasn’t publicly announced until after burial.

Sir John Robert Kerr (24 September 1914 – 24 March 1991) was an Australian barrister and judge

Whitlam and Fraser eventually became friends in the 1980s, campaigning together for the 1999 republic referendum. They never discussed November 11, 1975.

What Changes Came From the Dismissal?

The constitutional crisis prompted only minor reforms. The Senate retained its power to block supply. The Governor-General retained dismissal powers.

The main change was Fraser’s successful 1977 referendum preventing state governments from stacking the Senate with rogue appointments. That loophole had enabled the Coalition to gain Senate numbers in 1975.

Otherwise, Australia’s constitutional arrangements remained fundamentally unchanged. The system survived through an unspoken agreement: never again.

No Senate has blocked supply since 1975. No Governor-General has attempted dismissal. The crisis inoculated the system against repetition.

How Is the Dismissal Remembered Today?

The Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House marked the 50th anniversary with exhibitions, panel discussions, and special tours. Former Prime Ministers Paul Keating and John Howard both participated.

A new statue of Whitlam will be erected, commemorating his famous 149-word speech on the Parliament House steps.

Debate continues about whether November 11, 1975 represented democracy’s darkest hour or its salvation. For some, Kerr’s actions were an unforgivable assault on elected government. For others, they demonstrated constitutional safeguards working as intended.

Professor Frank Bongiorno from the Australian National University notes that today’s students find the events “fascinating in the way political science students did in the late 1970s,” though it feels like ancient history.

The Gough Whitlam dismissal created no consensus. Fifty years later, Australians still can’t agree on what actually happened or whether it was right.

Perhaps that’s the point. The crisis revealed that Australia’s constitutional conventions only work when everyone agrees to respect them. Once someone decides the rules no longer apply, chaos follows.

FAQs

Q: Why was Gough Whitlam dismissed in 1975?

A: Gough Whitlam was dismissed because the Senate blocked his government’s budget bills, creating a supply crisis. Governor-General Sir John Kerr used his constitutional reserve powers to remove Whitlam when he refused to call an election, arguing a government without supply cannot govern.

Q: Who dismissed Gough Whitlam?

A: Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed Gough Whitlam on November 11, 1975. Kerr was the Queen’s representative in Australia and held constitutional reserve powers to appoint and dismiss prime ministers in extraordinary circumstances.

Q: Was the dismissal of Gough Whitlam legal?

A: The legality remains disputed. Kerr’s reserve powers exist in the Constitution, but when they should be used isn’t specified. The High Court never ruled on the dismissal’s legality. The electoral defeat of Labor in December 1975 effectively settled the matter politically, if not constitutionally.

Q: What happened to Australia after Whitlam was dismissed?

A: Malcolm Fraser became caretaker prime minister, passed the budget bills, and called an election. His Coalition won a massive majority on December 13, 1975. Fraser governed until 1983. The constitutional crisis prompted minor reforms but left most powers unchanged.

Q: Did the Queen approve Whitlam’s dismissal?

A: Newly released archives from Canada reveal Kerr discussed the dismissal with the Queen’s private secretary before acting. The Queen’s office expressed approval afterward. However, the Queen maintained she played no direct role in Australian political matters.

Q: Has any other Australian PM been dismissed?

A: No. Gough Whitlam remains the only Australian prime minister ever dismissed by a Governor-General. The 1975 crisis was unprecedented and hasn’t been repeated in 50 years.

Q: What was Whitlam’s famous quote after being dismissed?

A: Whitlam’s most famous line was: “Well may we say ‘God save the Queen’, because nothing will save the Governor-General.” He delivered this speech on Parliament House steps immediately after learning of his dismissal.

Q: What reforms did Whitlam’s government introduce?

A: Whitlam’s government established Medibank (Medicare), abolished university fees, ended conscription, withdrew from Vietnam, dismantled the White Australia Policy, recognised China, and advanced Indigenous land rights. They enacted 508 bills in less than three years.

Q:Could the Whitlam dismissal happen again?

A: Constitutionally, yes. The Governor-General retains the same reserve powers. Politically, it’s extremely unlikely. The 1975 crisis created an unspoken agreement that such powers should never be used again. No Senate has blocked supply since then.

Q: What was the Loans Affair?

A: The Loans Affair was a 1974 scandal where ministers Jim Cairns and Rex Connor attempted to secretly borrow $4 billion from Middle Eastern sources outside normal government channels. The scandal damaged Whitlam’s government and gave the Coalition ammunition to block supply.

Q: Why is the dismissal still controversial 50 years later?

A: The dismissal remains controversial because fundamental questions were never resolved: Should the Senate be able to block supply? Should the Governor-General be able to dismiss elected governments? Was Kerr acting independently or politically? These debates continue to shape discussions about Australian democracy and republicanism.

Q: What happened to John Kerr after the dismissal?

A: Kerr resigned as Governor-General in 1977 amid ongoing controversy. He spent most of his remaining years living overseas. When he died in 1991, his death wasn’t publicly announced until after burial. Few people attended his funeral.